Brunel’s SS Great Britain:

The Ship That Refused to Be Forgotten

There’s something profoundly moving about standing before a ship that changed the course of history. The SS Great Britain isn’t just an iron hull or a relic from a forgotten century — she’s a living story of human ambition, innovation, and resilience.

When Isambard Kingdom Brunel launched her in 1843, the world had never seen anything like it. Imagine the awe that must have filled the air as this vast iron ship — the largest ever built at the time — slid into the water. People called her “the greatest experiment since the creation.” Brunel, with his trademark mix of audacity and genius, had defied convention. He built not from wood, but from iron. He installed a 1000-horsepower steam engine — the most powerful the sea had ever known. And instead of the familiar paddle wheels, he dared to try something entirely new: a screw propeller.

It’s hard to overstate what that meant. Brunel wasn’t just building a ship; he was reshaping the very idea of what a ship could be.

From Luxury to Loneliness

After her triumphant debut, the SS Great Britain’s life was anything but smooth sailing. Sold in 1852 to Gibbs, Bright & Co., she became a vessel of dreams for thousands of emigrants bound for Australia. The company modified her — adding a second funnel, an extra deck, and more efficient machinery — turning her into a ship that could carry up to 700 hopeful souls across the world.

Later, her decks held cargo instead of passengers: coal, wheat, and the weight of a world growing smaller through trade. She braved the wildest seas between England and America, until in 1886, the furious winds off Cape Horn finally had their say. Damaged and weary, she limped into the Falkland Islands. Her owners decided she wasn’t worth repairing.

And so began the long silence.

By 1936, the great iron ship lay abandoned on a lonely shore at Sparrow Cove, her hull split, her fittings stolen, her decks visited only by penguins and the occasional picnicker. It seemed that Brunel’s masterpiece had reached her quiet, inevitable end.

The Letter That Changed Everything

But history has a way of rewarding those who care enough to remember.

In 1967, a British naval architect named Dr. Ewan Corlett wrote a letter to The Times newspaper. In it, he argued passionately that the SS Great Britain was every bit as important as the Cutty Sark — that she deserved to be saved. His words struck a chord. Soon, people from around the world joined the cause.

Two years later, thanks to the generosity of philanthropist Jack Hayward, funds were secured to bring the ship home. The rescue effort was immense. Divers worked in brutal conditions, plugging holes and pumping water until the Great Britain could finally float again. On 24 April 1970, she began an extraordinary 8,000-mile journey back across the Atlantic — the longest tow in maritime history.

When she finally sailed beneath the Clifton Suspension Bridge and back into Bristol, millions watched, both in person and on television. The great ship had come home.

Alive Once More

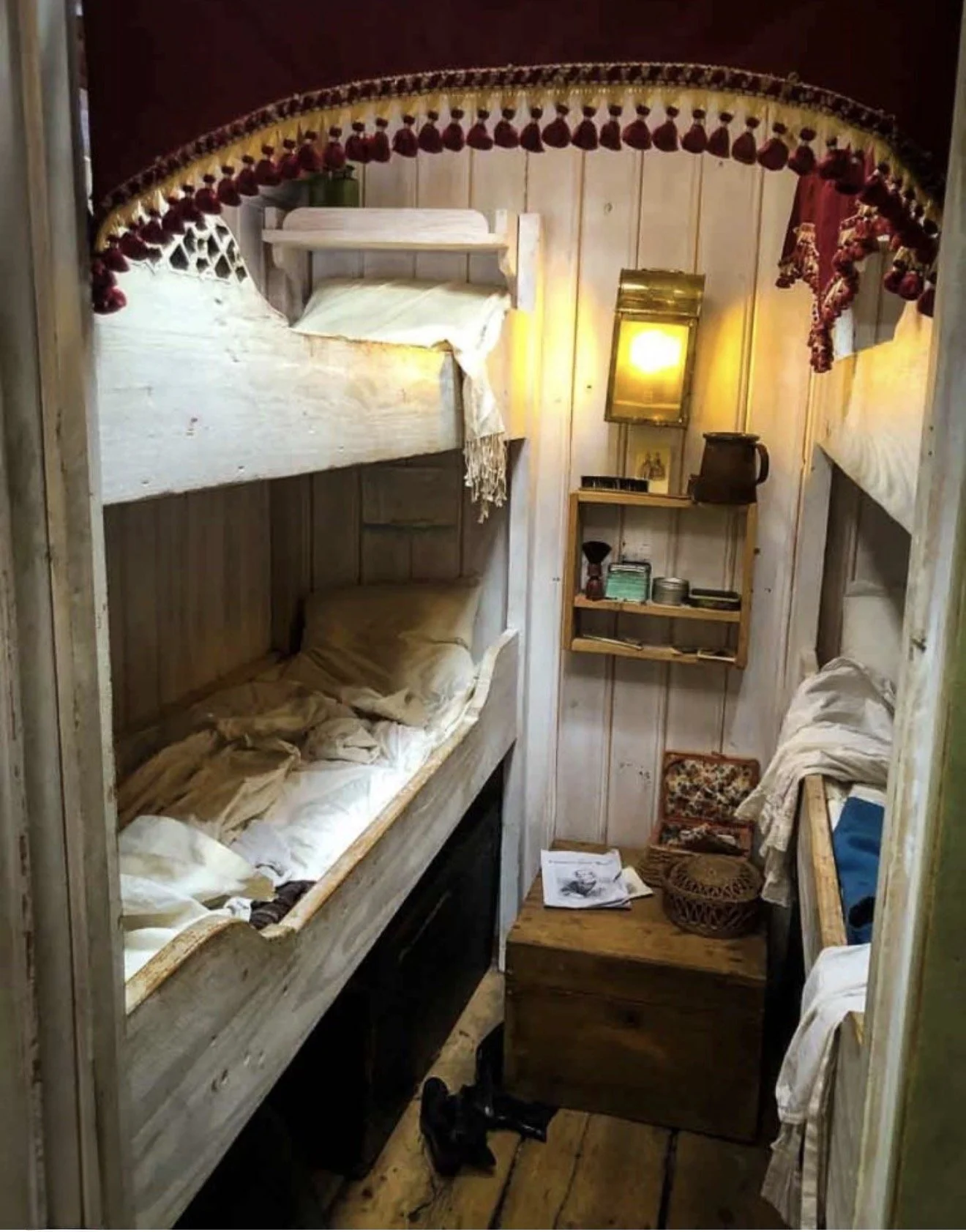

Today, Brunel’s SS Great Britain stands proudly in Bristol’s harbor — not just as a museum piece, but as a living reminder of human ingenuity. The ship and her surrounding museums are alive with the sounds, sights, and even smells of Victorian life. You can walk her decks, peek into the cramped bunks of emigrants, and imagine the salty wind that once filled her sails.

The SS Great Britain Trust continues to protect her legacy, inspiring new generations of engineers, dreamers, and adventurers — the very kind of minds Brunel himself would have admired.

A Legacy Forged in Iron and Hope

What makes the SS Great Britain’s story so powerful isn’t just her technology or her size — it’s her endurance. She was a product of vision, left to decay, and yet saved by sheer human determination.

Standing before her today, you don’t just see a ship. You see a mirror reflecting what we’re capable of when we dare to imagine, and when we refuse to forget.